The intensity of work since the start of the pandemic pushed Sarah “close to a breakdown”. The owner of a small UK-based business could not sleep or eat. “The pressure to keep the business going was all-consuming, I couldn’t take time off because I had hundreds of clients relying on me and looking to [me to] guide them through.”

Judging by a global survey by the Financial Times on work and mental health, to which more than 250 readers responded, Sarah’s experience was not unique. The respondents, who came from all corners of the world, were predominantly white-collar from sectors including education, financial services and media. They spoke of the difficulties — and benefits — of new work practices and about the demands spurred by the pandemic that have affected their mental health.

The pandemic has illuminated the areas of respondents’ lives — including career seniority, home environment and caring responsibilities — that have had an impact on people’s ability to do their job. Surveys show that mental wellbeing varies across the world. Britons, according to research by YouGov, are the most likely to report that Covid has harmed their mental health (65 per cent) followed by those in Hong Kong (63 per cent), and Italy (62 per cent) — with Germans the least affected (44 per cent).

Tears, stress and feeling overwhelmed came up regularly. Some had to take time off due to burnout, others spoke of a lack of motivation, difficulty sleeping and increased drinking. “[I’ve] been ending the day by opening a bottle of wine [or] beer, which has quickly become a daily habit,” says John. In the US, Rachel says her runs are an outlet not just for exercise but so that her kids do not see her cry.

Yet there was also liberation for many workers who had swapped offices for their homes. They could set their own timetables, no longer tethered by the grind of the commute, eat meals with their families and exercise throughout the day. Some praised naps and the joys of watching Netflix in downtime.

Employers’ responses varied. Some proved empathetic, others definitely did not. As one respondent put it, the “workload is insurmountable and [there is] denial about the issues”, so that management deem the inability to “achieve the unachievable objectives” as a personal failing.

Here is what readers told the FT in confidence about working during the pandemic. We have used first names only, where we have been given permission, and anonymised some replies.

Stress and heavy workloads

Messages from employers to workers telling them to prioritise wellbeing were welcomed — so too the meditation sessions, apps, and offers of therapy. Claire in the UK said her employer could not have “done more in terms of offering support to people. It is championed from the CEO down. I have seen a side to [the organisation] I didn’t expect.” Clara took advantage of her financial services employer’s cognitive behavioural therapy, or CBT, sessions. “I wasn’t one for therapy, but once I embraced it I did it well.”

Yet such initiatives did not address the fundamentals.

Julia, based in the UK, says there was little understanding or support for people with difficult circumstances. “The assumption was we carry on more or less as normal and some projects ramped up, new initiatives were launched, which was all very exhausting.” For the early part of the first lockdown she was home alone with two children. “Being a worrier by nature, I found it hard to sleep, I was overworked, had palpitations and panic attacks and felt fatigued most of the time. I was fearing for my health and what my kids would do if I fell ill as my husband was stuck working abroad and couldn’t get back.”

Sympathy and wellbeing initiatives did not address her workload. “I received no support in the form of help with projects which were still expected to be completed by strict deadlines and no extra time allowance, which would have been really helpful. The expectations were in line with ‘normal life’, which it was definitely not.”

Then she caught Covid-19. Afraid of falling behind in her work duties, she worked through her illness. “As a result it took nearly two months to recover.” Such stories were not unique. Steve, who works at a bank, spoke of being sick with Covid over the Christmas period but had to carry on working as he was covering staff absences over the holidays. “I haven’t had time off to recover properly.” Another respondent considered taking sick leave so they did not have to respond to emails and could catch up with their work.

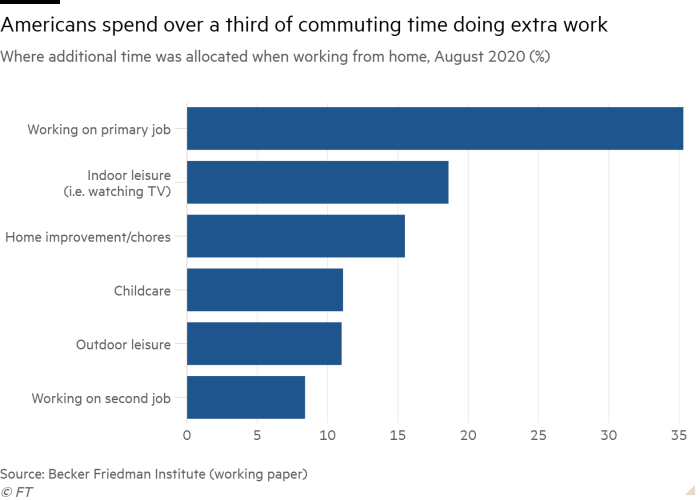

The overwhelming sentiment was that all the supportive messages and apps were ultimately meaningless if they did not address workloads. Many reported increased hours due to job losses, furlough and illnesses, while also struggling to keep businesses afloat. Research by Stanford University found that more than a third of Americans who were working from home last August spent the time they would have used on their commute doing extra work.

Readers told us about the stress of potential redundancies. A respondent said: “I have been told to work harder and smarter and if I don’t I can be replaced.” One man who works in financial services reports being so worried about losing his job he took just two of his 40 days accrued holiday.

Eva, a university lecturer in the UK, has been encouraged to speak up about struggling but feels like, “I can’t tell my boss, ‘Actually, I can’t teach because I’m overwhelmed and exhausted.’ It won’t be well perceived and if I do that then my teaching goes to my colleagues, which I don’t want either because it would overload them.”

Multiple tech tools meant that colleagues would often send the same message in different formats, at all hours of the day, which created problems switching off from work. One woman complained of a supervisor sending nine-page memos on Sunday nights, making it difficult for her to sleep.

Some respondents to the FT survey spoke of compassion fatigue. There was cynicism about HR initiatives as box-ticking led by executives more interested in signing up to charters than meaningful changes. Others highlighted the difficulties of speaking up about problems in a mental health session with 40 co-workers.

There were stories about co-workers who had taken time out for burnout and were then expected to resume normal service on their return.

Overseeing employees at a distance during unprecedented changes was challenging for managers. Some felt ill-equipped to deal with the demands of remote working and dealing with their teams’ mental health.

Lack of feedback

Remote working, particularly combined with social distancing and lockdowns, has created additional problems. The flipside of autonomy over working lives was a lack of feedback — some felt unable to judge how well their performance was received.

This was felt acutely by those new to a job. Maria, who started a new job in the infrastructure sector last year, says she lost confidence because she could not gauge how well she was “landing over video calls. I realised how much I rely on face-to-face meetings when I am establishing myself in a new job. Having to engage over video calls makes it doubly difficult: it’s hard to pick up on body language, so you have to ask for feedback directly, which in turn is harder because it’s a very intense medium for sensitive conversations.”

Parenting, isolation and generational divide

The stress of school and childcare closures has taken a toll on parents. Eva, the university lecturer, says she experienced burnout in July as she was doing too much and had to have time off to recover. “I feel physically and emotionally overwhelmed and exhausted.” For the moment, her children are in nursery. “I’m constantly worrying about whether my children are safe at nursery or whether I should have them at home with me.” Nonetheless, she feels like she is just surviving, “working and creating a happy home at the detriment of my own mental health. It’s not sustainable.”

Clara, in the UK, said that in the early stages of the pandemic she felt like she had “2020 responsibilities at work and 1950s home responsibilities”, combining managing a team with looking after a young child. “I don’t want my daughter to see that it’s always mum that does these things. I made a conscious effort to underachieve in certain areas, like cooking. If I felt my [male] colleagues were relying too much on their wife, I told them to take a day off.”

For Angela, despite splitting work and childcare with her husband, both work at night. “In most Zoom calls I had to bring my kids with me during the call. Can you imagine taking your kids to a work conference and you don’t know when your kids will throw a tantrum? It is simply impossible to look after kids while [working]. I feel constant guilt for my kids and also for work. I shout a lot more [at her children] than before and get frustrated.”

Parents, particularly women who have generally shouldered greater domestic responsibility, worry that it will have an impact on their careers. Eva, says she had to give up the research work as soon as the pandemic struck. “My children were at home with me and something had to give and it wasn’t going to be the teaching. The only person who is affected by me not doing research is me, not my employer. A year’s setback on my research is detrimental for my personal career.”

There was also a knock-on effect for those without children. Emily, who works in media in the US, says that her workload has easily doubled and on bad days, “quadrupled”, taking on tasks from colleagues who are parents.

“There’s nothing I can do to alleviate that — the work has to be done.”

Yet she feels that she has no right to complain or “even talk about my mental health” because she has no children. “It’s extremely difficult to talk about this, because of course I’m happy to help out and I know their lives are more difficult than I can even begin to imagine. I feel like I shouldn’t even be thinking what I sometimes think, which is that it’s like my life, mental health, stress [and] wellbeing doesn’t matter because I don’t have children. It makes me feel so guilty to say that and the guilt just compounds things.”

Loneliness is not just a social problem but also impacts her work. It has “made it difficult to focus”, she says.

There are also differences according to wealth and seniority. As Steve, the bank worker, says, “Junior/younger colleagues are in crowded house-shares, working from their bedrooms or on their kitchen tables or have returned back to their family homes to save rent. Senior/older colleagues are enjoying the lack of commute, more time with family and kids, more leisure time and chance to see their local area more than I have and have no urgency to return to the office. They have more space. Those making the key decisions on [a] return to offices are the senior colleagues who haven’t experienced the issues or ongoing problems of the juniors.”

Positives

Remote working was seen as an opportunity for many. Even those who felt stressed or isolated could separate the stresses of the pandemic from the benefits of homeworking, and hoped that when social distancing allowed greater movement that they would continue to work at least some of the time outside of the office.

Jenna felt liberated from her old working week, which used to be dominated by the minute hand. “Posturing is hard on a computer screen,” she added, echoing a thought expressed by others that it was easier to be judged by merit on their job when everyone was at home, rather than jostling for position in the office. Others spoke of feeling freer to be themselves at home and therefore more productive.

Autonomy allowed people to create their own schedules. Deanna, who runs her own business in the US, praised the joy of naps. One reader plans to work from a holiday destination. While Amy said that once she got over the guilt she learned to embrace flexibility. “If I feel chained to my laptop I become grumpy, whereas if I’ve had the chance to leave it and come back I feel more motivated. Sometimes I’ll be up at six doing three days’ work in just one morning. Other mornings I can’t be bothered to change out of my pyjamas.” Deleting her social media accounts had also helped.

Others have dealt with the inability to switch off by setting goals outside work, such as running and even creating a fake commute — a walk at the start and end of the day to create boundaries. Readers also praised bosses who offered regular one-to-one chats, as well as “walk and talk” calls that encouraged workers to leave their home offices.

Jules, who is on the autistic spectrum, discovered benefits to not being at the office. “I am particularly socially anxious . . . I used to be really stressed out about going out and into the open space in the office. Working from home has really improved my stress levels.”

In their own words — readers’ experiences

Liza, based in the UK says that mental health crises within her family meant that “work was a respite”.

Michelle in the US says: “I had two weeks of feeling overwhelmed to the point of going from my bed to my home office to my couch. No energy, silent migraines and depression.”

One respondent admitted he was relieved that the severe depression that had kept him off work for five months had not occurred during the pandemic. Yet even so, the workload rapidly piled up. “Preloaded with antidepressants and focusing on one day at a time, it just left me exhausted. Had it occurred at an early time in my illness, it would probably have been devastating.” His employer’s ambition to set one day a week aside as a rest day was great in terms of giving employees permission to stay off their emails, but “our workload hasn’t been cut”.

Ally, Switzerland: “My company has not given any credible/tangible support but my boss has been great; he has led by example and is always open for an informal chat.”

Jorge, Germany: “I can’t switch off from work because home is my work. I don’t have the break of a commute or the feeling that the day is over from leaving the office.”

Shanna, US: “I feel very, very burnt out but also extremely lucky and grateful to have a job. That, alone, is difficult to reconcile as so many are out of work, so I don’t feel I have a right to be miserable.”

Anita, Portugal: “I’ve been working far longer hours than before because most of my colleagues were put on furlough. I rarely take time off, even at weekends.”

Adam, US: “My wife and I find times to make up for lost ground occasionally by working in the evenings, which feels a little unbalanced but gives us a sense of accomplishment. I think we can make do until this is over.”

Kudzayi, South Africa: “I’m working impossibly long hours with no quiet times in between at all, but I have lots of support from work however and no real worries about losing my job.”

John, UAE: “My mental health has deteriorated on the back of constant zooming; I can barely find time to eat or work out.”

Jaideep, India: “The threat of losing my job hangs over my head like a Damocles sword.”

Additional reporting by Chelsea Bruce-Lockhart

Follow the topics in this article

Source: Feeling the strain: stress and anxiety weigh on world’s workers