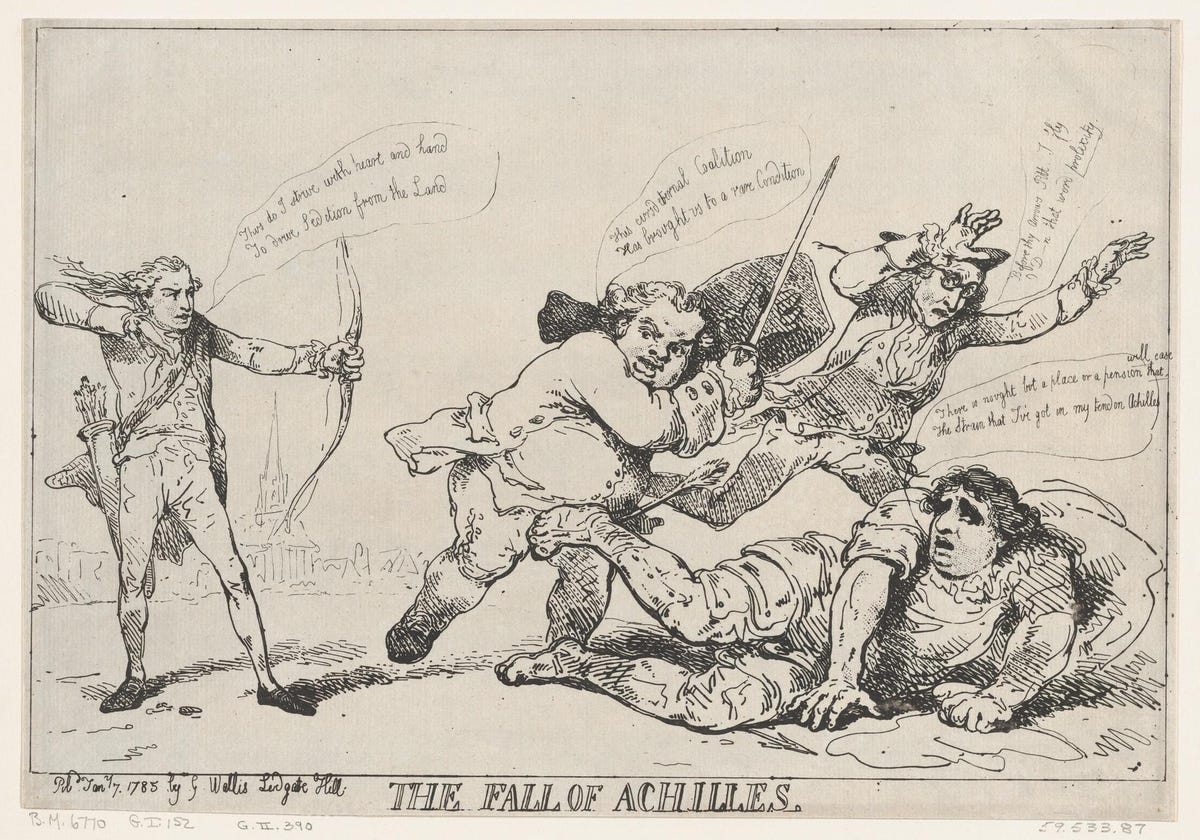

The Fall of Achilles, Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images)

Heritage Images via Getty Images

“Achilles heel” originated in Greek Mythology when infant Achilles was dipped in the Styx River by his mom to prevent his death at a young age, as foretold by the gods. It left the heel she held him by entirely defenseless. He became a great warrior who looked like Brad Pitt and survived many battles. But he was later killed by Paris (aka Alexander) when he was shot in his heel with a poisonous arrow during the Trojan War. The cool story became our best characterization of vulnerability.

Service processes, the hoops customers go through to get their needs met, may have a thoughtful and protective “mom” in the form of customer-centric leaders, but can still be the victim of an Achilles heel that robs them of their success. It could be the grumpy stock person in the aisle of a grocery store who throws rudeness at a customer seeking help locating an item. It could be a deceptive bill that entices customers to accidentally pay the past due amount printed in a larger type in the bottom right corner.

Wise organizations conduct service audits (with the help of customers) to spot glitches before they turn an otherwise positive customer experience into a dark memory. Here are five ways to avoid getting the “poisoned arrow” that can turn loyalty into abandonment.

1. Use the Longstreet Technique

When John Longstreet was the general manager of a large hotel near Dallas, he realized his front desk queries and guest surveys were not giving him the intelligence he needed to spot his hotel’s Achilles heels. So, he held quarterly focus groups with the taxi drivers who frequented his property to transport guests from his hotel to the airport. The time was pre-Uber/Lyft.

He quickly learned departing guests were far more candid with their taxi driver than with the “How was your stay?” question routinely asked at the checkout counter. Dust bowls under the bed spelled bugs in the room; slightly scorched-smelling towels triggered worries of a hotel fire started in housekeeping. The taxicab driver meetings enabled Longstreet to connect the dots between guest anxiety and solutions that nipped hiccups in the bud.

2. Hold What’s Stupid Meetings

Longstreet had another creative technique he used at his large hotel. On Friday mornings he held a “What’s Stupid” meeting with his hotel staff. It was not atypical for him to include a frequent guest or a regular vendor. The “anything goes” discussion enabled him to hear meeting attendees describe any policy, practice or viewpoint they perceived as “stupid,” especially those that impacted guests’ experiences.

“My job,” said Longstreet, “Was to listen, learn, record and then go to work fixing the irritants. At first, it was the predictable ‘breakroom Coke machine doesn’t work’ type complaints. But when the obvious glitches were corrected, the discussion turned to issues hidden from the eye of most hotel leaders. As a result, we all learned a lot about the concealed faults robbing us of both associate and guest loyalty.”

3. Be the Customer

There could be no more eye-opening learning opportunity than experiencing your service processes “like a customer.” When I worked with Ritz-Carlton Hotels, President Horst Schulze encouraged his hotel managers to visit other Ritz properties (as well as competitive hotels) to experience them more like a guest. “We cannot see our own foibles,” he would say, “But we are great at seeing the errors of others.” He was echoing the ancient proverb: “A guest sees more in an hour than the host in a year.”

Find ways to authentically test your service processes. When Erie “Chip” Chapman was the CEO of Riverside Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, he worked as a frontline employee one day each month. Donning the uniform of a maintenance worker, security guard, or cafeteria worker, he got an up-close-and-personal look at the real life his patients. Since patients assumed he was a frontline employee, they sometimes gave him an earful of “how they’d run the hospital”.

4. Ask the “One Thing” Question

Actor Jack Palance taught us in the movie City Slickers the power of “one thing.” Customers are too busy and lack the interest to answer many questions about their experiences. They ignore suggestion boxes as a useless exercise that never yields results. However, at the point of contact, there is often a chance to ask one simple question: “What is one thing we can do to make your experience a great one?” And there are many versions of that “one thing” question.

The “one thing” question is focused, efficient and typically timely. And if customers draw a blank on an answer to the question, suggest they “make something up.” It frees them from the pressure to be correct and typically results in a suggestion that addresses a legitimate complaint, issue or idea. Remember, this is not pristine scientific research; it is frontier customer learning.

5. Don’t Ask Unless You Are Serious

Research tells us that 95% of organizations have some way of soliciting customer feedback. About thirty percent take some action based on the input. But less than 5% respond to customers to let them know their input triggered an action. No wonder survey research considers a 20% response rate to a survey to be effective. What would it tell you if you surveyed your extended family on your family relationships and got back only one survey in five? You would probably label the family “dysfunctional.”

I recently had a troubling issue with my phone company of many years. I give them thousands of dollars each year. The issue was what I consider a moral issue over customer treatment. The following week I received a random lengthy survey. I gave them scathing, detailed feedback, including threatening to change phone companies. It was the kind of feedback that would make a CEO demand an explanation of underlings. But I never heard back. That same week I received their monthly bill.

Every organization has “gremlins” hiding in the shadows, waiting to turn a potentially cheerful experience into a customer calamity. Systems and processes are the product of people, and we all are imperfect. Just as the gifted and successful warrior Achilles had his small vulnerability that became his undoing, we must remain vigilant for the potential of our unseen foibles becoming our unexpected failures.